A recent fiscal report has unveiled a worrying trend in Nigeria’s public finance management — several states are piling up more debt even as their earnings from federal allocations continue to rise. The development has raised fresh concerns over the sustainability of sub-national borrowing and the potential long-term strain on Nigeria’s public debt profile.

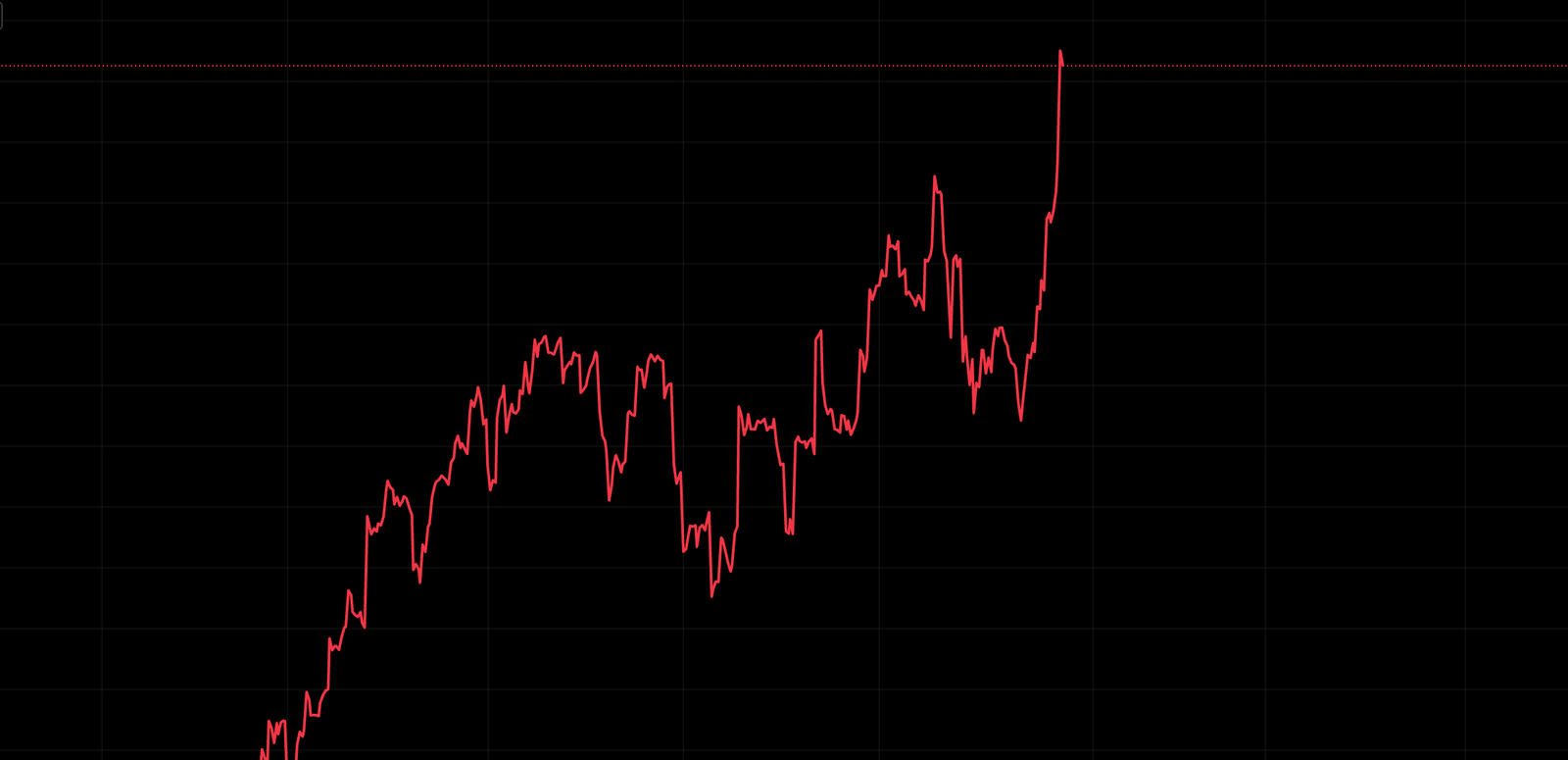

According to the latest data analysed by Bizwatch Nigeria, ten states — including Rivers, Enugu, Niger, Taraba, Bauchi, Benue, Gombe, Edo, Kwara, and Nasarawa — collectively increased their domestic debt stock from approximately ₦884.9 billion in the first quarter of 2024 to about ₦1.30 trillion in the same period of 2025. This represents a sharp year-on-year increase of nearly 47.2 percent, despite the rise in statutory allocations from the Federation Account Allocation Committee (FAAC).

Further breakdown of the report shows that Enugu State recorded one of the steepest increases, with its debt stock jumping from ₦82.48 billion to ₦188.42 billion — a rise of about 128.4 percent. Taraba State followed closely, posting a 154.1 percent surge within the same period. Other states such as Rivers, Edo, and Benue also witnessed notable spikes in their debt profiles, contributing significantly to the total domestic debt accumulation across the federation.

Despite these increased earnings, many states are struggling to balance their books. The report indicates that the rise in debt levels is not merely a function of low revenue but also of fiscal mismanagement, poor expenditure control, and increasing recurrent obligations. In several cases, debt servicing costs have now surpassed the states’ internally generated revenue (IGR), leaving little fiscal space for capital development and public investment.

Data from the Debt Management Office also reveals that while the monthly allocations to states have risen nominally, inflationary pressures and the depreciation of the naira have eroded the real value of these funds. As noted by The Guardian Nigeria, the apparent revenue growth is largely a “money illusion,” as states are forced to spend more to achieve the same level of service delivery due to surging costs of materials, wages, and infrastructure inputs.

This situation has created a paradox in Nigeria’s fiscal structure. Although increased allocations were expected to ease the financial burden on states and reduce their dependence on loans, the opposite has occurred. Many states have resorted to borrowing not just for capital projects but to finance recurrent expenditures such as salaries, pensions, and administrative costs. This borrowing pattern has raised fears of a deepening fiscal crisis, with experts warning that the trend could threaten both state-level and national debt sustainability.

Analysts attribute part of this problem to weak financial discipline, limited transparency in the use of borrowed funds, and the lack of accountability mechanisms at sub-national levels. With debt servicing obligations consuming a growing share of revenue, development projects are being stalled or abandoned across multiple states, further worsening the infrastructure deficit.

While the federal government has continued to disburse increased allocations amid rising oil receipts and improved non-oil revenue collection, many states have failed to use these funds prudently. The resulting fiscal pressure, compounded by inflation and a weakening currency, has led observers to warn that Nigeria could be entering a dangerous cycle of debt dependency, where states borrow not to invest, but merely to survive.